https://www.ft.com/content/45d0a047-360f-4abf-86ee-108f436015a1

Content and copyright all from FT.

The suicide of Alex Kearns — who thought he had lost heavily — has triggered calls for reform of online brokerages

Robin Wigglesworth in Kragero, Richard

Henderson in Melbourne and Eric Platt in New York

JULY 2 2020

Alex Kearns was an ordinary 20-year-old. He

played the trombone, studied at the University of Nebraska and, like millions

of other Americans, traded stocks to pass the time or make some money when

coronavirus shut down schools and workplaces. Unfortunately, his youthful

dabbling ended in tragedy.

On June 12 back at home in Naperville, Illinois, Kearns took his own life, after believing he had lost nearly $750,000 in a soured options bet made on Robinhood, an online brokerage that has become emblematic of a new era in retail investing.

In a note left for his family, Kearns said he had “no clue about what I was doing” and never intended to “take this much risk”. Horrifically, it appears Kearns mistook the potential loss on one leg of an options trade for the outcome of the overall bet — wrongly believing that he had racked up a loss of $730,165. In fact, his account had a balance of $16,000.

The tragic episode highlights the dark side of the recent boom in retail trading and the offerings from online brokerages — such as free trading, options, cheap debt and the ability to buy small slices of stocks — which have lured more investors to the markets. Some observers worry the new class of e-brokers have helped turn the experience into something akin to a video game, with constant updates about profits and losses and social media fuelling the frenzy.

“The more I dug into it, the angrier I got,”

says Bill Brewster, an analyst at Sullimar Capital in Chicago who is married to

Kearns’ cousin and speaks on behalf of the family. “They’re almost pushing

people into financial dynamite.”

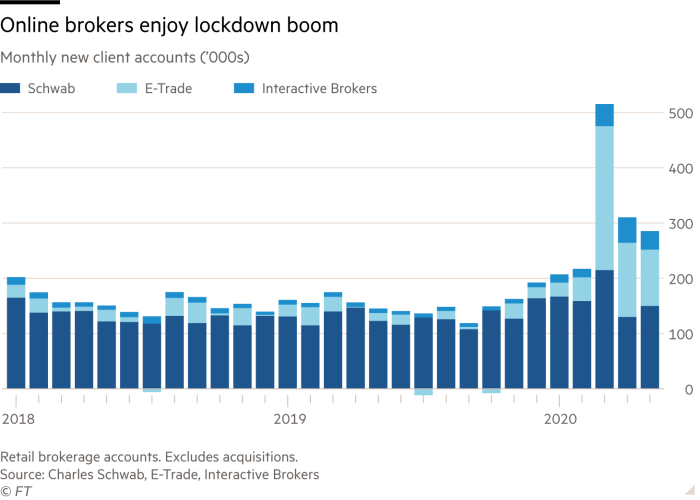

The surge in retail trading has been a boon

to brokerages. Robinhood added 3m users in the first quarter, pushing its total

number of users above 13m. Schwab, ETrade and Interactive Brokers together

added 1.5m new accounts in the first five months of the year, nearly double the

amount for the same period in 2019. TD Ameritrade, which shares quarterly data,

added more than 500,000 new accounts in the first quarter — three times the

amount for the same period a year earlier.

Vlad Tenev and Baiju Bhatt, the co-founders

of Robinhood, said they were “devastated” by Mr Kearns’ death, and vowed that

the company would expand educational resources related to options trading,

tweak the app to clearly show users’ financial exposure when making options

trades and would consider adding new criteria for customers to trade

sophisticated options.

Congressman Sean Casten of Illinois last week

raised the tragedy with Jay Clayton, the head of the Securities and Exchange

Commission, who said regulators were looking at how to improve disclosure. “I

read it over the weekend and it’s terrible,” Mr Clayton said. “We need to do

something to make sure these kinds of things don’t happen.” Mr Casten later

tweeted: “Democrat or Republican, Alex could have been any of our kids. It’s

time for the Senate to act.”

Mr Brewster lauds the changes promised by

Robinhood, but remains worried about how it and other platforms have

transformed trading and sucked in younger, inexperienced and potentially

vulnerable people.

“It’s the beginning of a long journey, not

the end,” Mr Brewster says. A broad discussion is needed about the downsides of

giving everyday investors unfettered access to the markets, he adds. “Have we

crossed the Rubicon into dangerous territory? I think we probably have.”

SEC chairman Jay Clayton testifies last week before the House Committee on Financial Services hearing, ‘Capital markets and emergency lending in the Covid-19 era’. He said regulators were looking at how to improve disclosure © Rod Lamkey/Getty

Video game Icarus

Berkshire Hathaway’s famously acerbic

vice-chairman Charlie Munger made his views on day traders and their enablers

clear at last year’s annual meeting of the Daily Journal, the publisher he

chairs.

“I regard that as roughly equivalent to

trying to induce a bunch of young people to start off on heroin,” he told the

attendees. “It is really stupid.

” Mr Munger was not far off. Research by

neuroscientist Hans Breiter shows the same part of the brain activated by drugs

like cocaine is also triggered when a person anticipates a financial gain. That

has been supercharged in the new era of online trading platforms.

The neon colours and slick interface of

Robinhood, as well as its pitch to users to “level up with options trading”, is

a step change from the relatively sedate websites of its older rivals such as

ETrade and Charles Schwab. New users are given a free stock — usually valued

below $10 — to get them started, and confetti blasts across the screen when

users make their first stock and option trades.

“The parallels between video games and day

trading is becoming closer and closer,” says Andrew Lo, a finance professor at

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “For many gamers, particularly the

younger ones who are not used to trading and don't fully understand the impact

of significant losses and gains on their psychophysiology, it could have some

significant adverse consequences.”

According to Prof Lo’s studies of traders,

the consequences include fear, anxiety, regret, frustration and disappointment,

and even symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder for those who made large

losses early in their careers.

Vlad Tenev and Baiju Bhatt are co-chief executives and co-founders of Robinhood Financial

© Alex Flynn/Bloomberg

The ‘gold’ membership allows traders to make bigger bets with money borrowed from the company © David Paul Morris/Bloomberg

In the past, getting signed up to an online

brokerage could be fiddly and take time. But the technology has moved on and

today, it can take just minutes to sign up for an account in the US. Broker

approval usually takes a day, opening the door to trade in stocks and exchange

traded funds. Traders can then seek approval for more advanced instruments,

such as options or borrowing money on “margin”.

For example, Robinhood traders can sign up to

its “gold” membership, which costs $5 a month after a free 30-day trial. This

allows traders to make bigger bets with money borrowed from Robinhood. The only

restrictions are that federal regulations require a trader to have at least

$2,000 in their brokerage account and “a suitable investment profile in order

to use margin”, which Robinhood determines with a few questions on the trader’s

experience, aims and sensitivity to risk.

Analysts say the use of options can be

particularly dangerous. Options are a financial derivative that can give

investors far greater exposure to a stock or equity index falling or rising

with an often minimal downpayment, magnifying gains but also potentially

enhancing losses.

The retail trading frenzy has already helped

trigger a surge in option trading this year, with the total value of contracts

now at $5.2tn, roughly double the level seen five years ago, according to

Goldman Sachs. That is a sum equal to about 20 per cent of the overall stock

market value of the S&P 500 benchmark of US blue-chip companies.

Researchers at Allianz, the German insurer,

noted that single contracts — most popular with smaller individual traders —

accounted for 13 per cent of S&P 500 options volumes traded since March, up

from about 8 per cent a year earlier. For some stocks popular among day traders

— such as Chipotle, Amazon and Tesla — single contracts account for between 20

per cent and 30 per cent of the option volume.

“One only has to spend some time on popular

Reddit communities to get a broad idea of the current market hysteria and the

risks that ‘new retailers’ are taking,” Allianz said in a report in June.

Bill Brewster lauds the changes but says ‘it’s the beginning of a long journey’

The e-brokers have statements stressing that

options trading entails significant risk and is not appropriate for all

investors, directing people who want to learn more to a 26-year-old paper —

last updated in 2012 — from the Options Clearing Corporation about the

potential pitfalls.

Retail brokers are required to set different

levels of options trading available to customers, who apply for permission to

move from one tier to another based on factors such as how long they have

traded, net worth, liquid assets and age. The e-brokers typically have

three or four different levels but do not disclose the requirements for each

tier to avoid users gaming the system.

The brokerages are also subject to rules that

require investors classed as day traders, under a regulatory definition of four

trades in and out of a stock in one day across five trading days, to hold at

least $25,000 in equity in their accounts. Brokers said in statements to the

Financial Times that they adhere strictly to regulatory guidelines, ensure that

only suitably experienced traders can get access to more complex option

strategies, and provide plenty of free education for traders.

The neon colours and slick interface of Robinhood, as well as its pitch to ‘level up with options trading’, is a step change from older rivals’ websites © Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg

The company vowed to tweak the app to clearly show users’ financial exposure when making options trades © Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg

The retail trading phenomenon has been so

strong that even professional investors have had to adapt to its warping

effects. Max Gokhman, head of asset allocation for Pacific Life Fund Advisors,

a US fund manager, says he has now been forced to consider the impact of retail

trading in companies that have become popular among everyday investors — such

as airline stocks and Tesla.

Mr Gokhman likened professional investors to

pilots manning a jumbo jet, while the retail traders are Icarus, the mythical

Greek figure with wings of wax, flying alongside. “We know we can move altitude

up and down and have sophisticated systems to change our exposure,” Mr Gokhman

says. “But Icarus is just getting higher and higher, closer to the sun and

inevitably Icarus — in this case the day traders — will crash.”

Options risks

Even some veteran day traders are shocked at

the current frenzy. Marcello Arrambide, who runs Day Trading Academy to train

and funnel promising stock jocks to his trading platform SpeedUp Trader, thinks

that the current market euphoria, and the day-traders it has buoyed, will end

in tears.

“The barriers are now so low that anyone can

come in and think they can do it. You can’t lose right now, and that’s the

problem,” he says. “The amount of people that are going to get wiped out when

the market does fall is going to be ungodly.”

Mr Arrambide refuses to teach traders to use

options, preferring to concentrate on stocks and futures, and is in favour of

restrictions on their use for retail investors, given the complexity and

potential pitfalls. “But if it isn’t trading, it would be something else,” he

adds. “People just want to get rich quick.”

Terrance Odean, a finance professor at the

University of California at Berkeley who has studied day traders, says more

education is needed. “If it’s play money and money you can afford to lose,

that’s your business. But you don’t commit suicide because you lost your play

money,” he says. “I would hope the vast, vast majority of investors writing

unhedged calls and puts understand the risk but I assume there are some who

don't . . . it wouldn’t be horrible to give people five minutes of education.”

Study after study in various countries

demonstrate that the overwhelming majority of day traders end up losing

money.

A recent study of retail investors in Brazil

between 2013 and 2015 found that 97 per cent of those that traded for at least

300 days lost all the money they had put up. Only 1.1 per cent made more than

the Brazilian minimum wage, and only 0.5 per cent earned more than an

entry-level bank clerk.

The impact of trading on people’s health can

also be marked. Big stock market drops are associated with worsening mental

health, spikes in binge drinking and fatal car accidents involving alcohol,

according to a study from the University of Chicago.

Trading may seem like a sedentary job, but

the stresses can even have physiological effects, such as higher blood

pressure, Prof Lo says.

“Trading is a physiologically taxing

activity,” he says. “You may not think that, because what are you doing?

Sitting at a desk and shouting numbers into a phone or entering orders

electronically. But the amount of stress that trading imposes on the human body

is very significant.”

Family left with questions

Mr Brewster says none of the family are aware

of any other underlying reasons why Kearns might have chosen to take his life.

He had previously known the young student as someone who would always play with

everyone’s kids at family gatherings, but in March he had approached Mr

Brewster to talk about stocks, the Federal Reserve and the outlook for the

economy.

“It seemed like his life was in a good spot . . . It

was the first time we really talked as men,” he says. “Now we’ll never be able

to do it again.”

There are not thought to have been any other underlying reasons why Alex Kearns might have chosen to take his own life © Kearns Family

The loss has galvanised him, and he now wants

to spark a broader debate about the side-effects of gamifying trading that have

emerged as the dark side of “democratising” investment, as proponents frame it.

The Kearns tragedy may be uniquely awful but Mr Brewster frets that the

problems he faced will be far from uncommon, given the recent day trading

frenzy.

“I think people are making massive mistakes

and ruining their financial futures,” he says. “The societal consequences could

be huge down the line.”

No comments:

Post a Comment